J. J. French

Storyteller

Virtual photography

This is an infrequent hobby of mine. From 2017 to 2019 I was trying to break into the game industry as a lighting artist. Ultimately the junior-level job opportunities that did come my way in that career path simply did not pay enough to cover my rent, so I took a different, more corporate path when it came to making a living. But during that push I needed the beginnings of a portfolio, and those beginnings turned from something I did to get a job into something I did just because it was fun. A game engine like Unreal, with its multitude of lighting, FX, and rendering features, makes for a pretty solid workstation app for this sort of thing. In effect I'm putting together a slice of a game environment, or perhaps more accurately a game cinematic environment, minus the game itself. However, working in a game engine, which is inherently geared for interactive play, means dealing with a multitude of shortcuts that make it possible to show a new image, or frame, of a game on your screen at least 30 times in 1 second, rather than doing things "properly" and showing 1 new frame every 30 seconds. Games are carefully orchestrated piles of cheats, hacks, shortcuts, and duct tape, and the best-made ones deftly embrace that fact. Lighting artistry is no exception.

"Night Rider", October 2018 - Baked lighting. The shadows and shot composition are doing most of the work here.

Just a handful of years ago the standard method of lighting a game environment was to fake hyper-detailed illumination by doing an offline calculation (called 'building lighting') to 'bake' a pretty accurate picture (called a 'lightmap') of light and shadow into each surface of the world. Baked lighting was essentially unchangeable without being rebuilt, so if you wanted interactivity with your lights (such as a working light switch or a flashlight), game engines would provide various mechanisms for dynamic lighting and shadowing. Dynamic lights (and the shadows they create) would be able to move, change in brightness or color, and be used for interactive gameplay in combination with baked lighting, but were relatively intensive, so you rarely saw lots of them used at the same time. All of these lights, both baked and dynamic, came from deliberately placed 'light actors' that you'd put into the game world kind of near to whatever prop was meant to be the source of the light. If, for example, you had a nice generic fluorescent ceiling light in your game world, in order to make it behave realistically you'd have the model of the light fixture, and then an invisible light source floating around or in front of it to send light out into the world.

Along the way, GI - or 'Global Illumination' - systems would work out how the light from those hand-placed sources in your world should bounce around a bit, and try to give it that extra little bit of realism. GI systems help a lot with letting light naturally and compellingly spill through a room and covering up the shortcuts you need to take in the name of expediency. As an artist you probably wouldn't bother adding a unique light source for every LED on a piece of tech, and just leave that kind of detail out, because rebuilding lighting took ages. It was slow. So the less artistic stuff there was in your scene for you to fine-tune, the faster your project could go. All of this is to say that in those recent-enough days, lighting in games was both extremely deliberate and extremely inflexible.

"1:53 AM", May 2020 - Baked lighting. Not the most focused scene, but carefully calibrated to hint at parts of the world you can't see.

But light in the real world doesn't really work that way. In the real world, light is accidental, comes from a multitude of sources big and small. And for the last couple years, the newest versions of Unreal Engine have included a very different approach to lighting, which the engine's developers at Epic Games call Lumen. Lumen is one of a new breed of light-rendering systems - often you'll see this kind of thing advertised as ray tracing, and usually it is or is closely related - that behave rather like those used in TV and film (think Pixar's RenderMan). That means that all the rules for how you put light into a game scene are wildly different now. Systems like Lumen don't treat light as something that's painted into every surface of the world; they instead treat light as something that comes from and moves through the world. In Lumen, there are no hand-placed light sources; if the LED on a piece of tech looks like it glows, it actually is glowing. The fluorescent light fixture casts its cold light into the world simply by looking bright, with no further fakery required. The GI effect of lighting spilling around a space just happens. In this system, iteration is instantaneous. Reader, I cannot stress enough how much this matters for the process of making these onscreen worlds; not only is it tremendously faster to make things look pretty in the first place, every single source of light in the world can move, or change, or be interactive.

However, Lumen and its ilk are still fundamentally shortcuts, and that means the challenges for working with them are still there. With baked lighting, the shortcuts (sometimes called "optimizations") that can be taken to improve real-time performance or squeeze your game into less disk space are fairly harmless; with Lumen, it is, broadly, either a matter of living with a demanding, high quality image, or watching your game world disintegrate into a fizzling Rorschach-inspired fever-dream. It is very demanding on the hardware we use to play games. And this is OK! Every new technological leap goes through growing pains, and when this new approach to lighting is at its best, you never even think twice about it. You need only look at a game like the exemplary Indiana Jones and the Great Circle to find an example of how this can help free up a game to give the player beautiful visuals and lots of interactive stuff at the same time. (Great Circle is not an Unreal Engine game, but it is built using similarly modern technologies).

For me, all this stuff is very neat. In May 2025 I don't work on games for a living. When you get to it, for me this is all just the means to making a pretty picture, and when I sat down to make a new one last night, I was delighted to find how much more quickly I could work. I don't have as much time for creative pursuits these days as I used to, so, fundamentally, Lumen was the difference between actually getting to craft the scene in my head and having to resignedly say, "Oh, I'll get back to this tomorrow and do that bit if I have time." Kudos to the clever people that invented it.

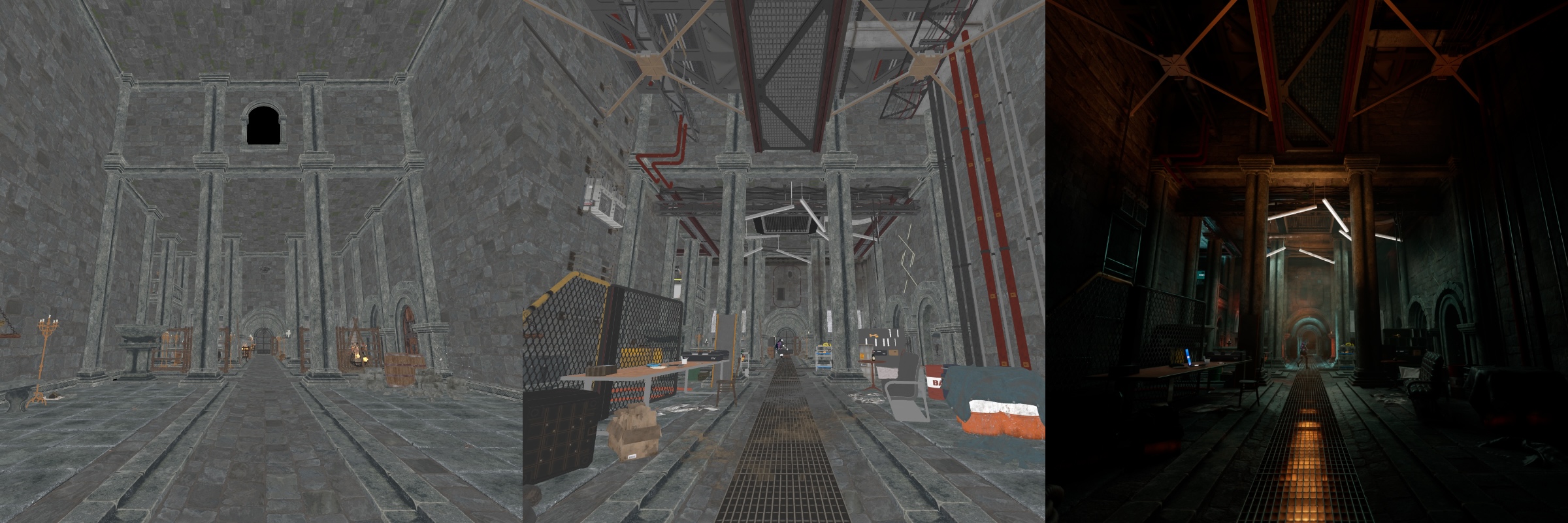

Left to right: Off-the-shelf dungeon asset pack, to fully decorated, to fully lit.

"Underground", May 2025 - Lumen lighting. Gothic meets cyberpunk, sorta. This was fun!